|

Now Buy the Hard

Copy!

Amazon

USA

Amazon

UK

BULLETINS

The

most recent Newsletters are available by private subscription

Info

and Order

Check out Geoff's

Latest Book!

Nutritional

Anthropology's Bible:

DEADLY

HARVEST

by

Geoff

Bond

COOKBOOK

Healthy

Harvest Information Page

|

How it was before

We

know quite a lot about the location of the birthplace of the human race.

Even in Victorian times, when the great apes, the chimpanzee and gorilla

were first discovered in equatorial Africa, some researchers speculated

that this too was the birthplace of mankind. Over the intervening years,

fossil evidence came to light that reinforced this theory.

Much more dramatically, in the last few years evidence has come from a

totally new direction, DNA analysis. It is now clear that everyone on

this planet is descended from a group of ancestors that lived in the

savannahs of East Africa some 80,000 years ago. It even appears that we

are all descended from just one woman who lived in the group 100,000 to

150,000 years earlier, the so-called ‘Eve’ hypothesis. There was not

necessarily anything special about her. It’s just that the blood-lines

of all the other women of the tribe have petered out down the

generations.

At that time the total world population of humans was probably no more

than about 10,000. And how were they living? We can now get a good idea

from a number of areas of research. For example, by studying such

features as teeth and jaws, we know that they were designed for a

particular kind of eating pattern. There are even studies of enamel

thickness, tooth wear, micro-scratches and striations that can be

matched with known patterns today.

There are studies of the vegetation that grew in the area at the time,

and of the animal life that abounded then. Calculations are made as to

the most efficient use of energy expenditure to gain food. (It is

assumed that, back then, our ancestors were no more inclined to work

than we are today.) For example hunting is a high energy expenditure

with an uncertain reward. It is also risky. Rather than getting

dinner, the hunter could finish up as

dinner. Foraging for nuts, fruits, tubers, roots, flowers, edible

gums, shellfish, caterpillars, was much surer, safer and energy

efficient.

The forensic archaeologists can tell a lot from both human and animal

bones. Early humans were tall: Turkana boy, only about 12 years old,

would have grown to 6 feet. We can tell a lot about the diseases they

suffered and didn’t suffer. For example, osteoporosis, gallstones,

kidney stones, arthritis and dental caries (cavities) were virtually

unknown.

It is possible to tell something from the animal bones that are found at

ancient human encampments. Were these animals killed by humans? If so,

were they killed for food? Or were these animals killed by some other

predator and only then butchered by humans? Or was the animal killed by

a leopard and dragged to the same leafy spot occupied by humans 20 years

previously?

Mostly it is impossible to know from a pile of animal bones,

accumulating over millennia, who ate them, let alone what proportion of

the diet they represent. After all, bones fossilize very well,

vegetation doesn’t fossilize at all.

Nevertheless clever analysis can cast some light on what really

happened. For example, prey bones often bear scratch marks. Some of them

are from the teeth of the predator that killed them, some are the marks

of a stone tool. Sometimes they occur together. It is possible to

discern which came first, the lion’s tooth-marks, or the stone knife.

The studies to date suggest that humans mostly chopped the meat after a

predator had first killed it.

This is not surprising. Back then there were no real weapons, not even

bows and arrows. All that Pleistocene humans had were sharp sticks,

sharp stones and their bare hands. The savvy strategy to procure meat

would be to fight off the hyenas and vultures for the carcass of an

animal brought down by a specialist killer, such as a lion.

If humans were eating meat, how important a part did it play in their

diet? And what was it like? There is still a vigorous debate over the

first question. There were times of plenty and times of food stress.

What is very clear is that humans were eating animal

matter in significant quantities – say 20% of their diet. But

notice the words ‘animal matter’. A large part of their consumption

would have been made up of lizards, snakes, bugs, caterpillars, frogs,

insects, shellfish, eggs, and, yes, small game and carrion.

There is less debate about the nature

of this animal matter. There are three remarkable features about it:

it was very low fat – no more than 3% (as against 25% fat in modern

beef).

the fat was very low in saturated fat and high in ‘essential fatty

acids’ (exactly the opposite of modern supermarket meats).

the essential fatty acids were present in a well defined ratio of

linoleic acid to alpha linolenic acid. The range of this ratio varied

within close limits of between 4:1 and 1:1. It transpires that this

fatty acid profile is exactly the profile that we modern humans need

too. In the average western diet this ratio is totally distorted at

32:1, and we know that this has harmful health effects. More of this in

Chapter Five, How and What we Eat.

But let’s look a little more at these essential fatty acids. They are

so important that they used to be called vitamin F1 (linoleic

acid) and vitamin F2 (alpha linolenic acid). All the other

fatty acids that human biochemistry needs can be made by the body from

these two.

But why these two fatty acids in particular? The body never had to learn

how to make them. They were always

there in the diet. They were in the plants that the herbivores ate,

so they were there in the herbivores that the carnivores ate, and

ultimately they became part of the carnivores too. Those fatty acids

were omnipresent in the whole nutritional environment – and in that

ideal ratio range of between 4:1 and 1:1 to boot!

A similar phenomenon is found with vitamin C. Humans, along with most

other primates, are the only creatures that cannot make vitamin C in

their bodies. This is not a fault, it’s just that our bodies never had

to learn to make it. Vitamin C was

always present in the diet from the fruits and vegetation.

The body’s need for these three vitamins (C, F1 & F2)

alone tells us a lot about our Pleistocene ancestors’ eating patterns.

A

hunter-gatherer needs a range of about 5 square. miles to feed himself.

The maximum population that the continental

United States could support like that is 600,000 hunter-gatherers.

Compare this to the current US population of some 260 million.

There is no going back!

How

exactly did our ancestors, live all those generations ago? We are now

able to piece together a clear picture. They lived in groups of 35 to 50

people – men, women and children together. This group would have a

territory of 200 to 300 square miles that they defended fiercely from

incursions by neighbouring groups. Within this territory they wandered.

These people had no clothes and no possessions. According to the

availability of the food supply they camped and then moved on – every

day if need be. They had no permanent shelter. Each night they would

hunker down under a bush and maybe pull some branches over into a

make-shift shelter.

They had fire and used it for light, warmth, cooking meat, and for

firing the bush to chase out small animals. These people didn’t plant,

didn’t conserve, didn’t save but they did make a mess wherever they

went! They didn’t wash, smelled like pole-cats and lived in relative

squalor. And yet they were healthy and had good longevity. They had few

predators and were much more likely to be killed by warfare with

neighboring groups. It has been estimated that their percentage

casualties per year were as much as those of the German population

during World War II.

It is thought that much of the time, our early hominid ancestors

fulfilled their basic protein needs just by consuming plant foods.

These peoples had a choice of hundreds

of edible plants, a rich variety compared to the 30 or so found in

today’s supermarkets. The adjacent table itemises some important

nutrients found in a basket of just 50 forager plant foods.

|

Average

of some

50 Wild Vegetable Foods

consumed by foragers.

Values for 2 kg

|

|

Protein

|

g

|

82

|

|

Fat

|

g

|

56

|

|

Carbohydrate

|

g

|

460

|

|

Fibre

|

g

|

62

|

|

Energy

|

kcal

|

2600

|

|

Calcium

|

mg

|

2000

|

|

Potassium

|

mg

|

9800

|

|

Sodium

|

mg

|

210

|

|

Vitamin

C

|

mg

|

540

|

| |

Yes, protein is in

vegetables too! 82g of protein are plenty for the average adult.

Better still, it is absorbed in small doses throughout the day. Not a

sudden, calcium depleting, kidney-bashing, amino-acid rush as happens

when a large steak is eaten. Indeed, on average, Americans consume twice

the amount of protein thought advisable.

Not only is there plenty of protein, there is plenty of calcium, yet not a glass of milk in sight.

Potassium is very high by

western standards – and not a banana in sight either. (Bananas are

native to Indonesia, not Africa.)

Sodium is good and low. After

all, they had no added salt and no processed foods. Sodium intrinsic to the plant, was the only sodium in the diet.

More interesting is the ratio

of potassium to sodium – about 40:1. The potassium/sodium ratio is

important to keep electrolytes balanced at the level of cell metabolism.

Get it wrong, and the heart stops beating, nerves stop functioning and

muscles shut down. Get this ratio wrong in the diet, and the body

particularly the kidneys, is battling to straighten it out. Today’s

Western diet reverses the desirable ratio. It is now known that this chronic

imbalance in the potassium/sodium ratio is a factor in many

cardio-vascular diseases, such as stroke, high blood-pressure, cardiac

arrest and inelastic arteries.

Note that our ancestor’s high potassium intakes came from vegetation.

And the low sodium levels from the absence of table salt.

As for vitamin C, see what a

high level it is – 540mg. There is ample evidence that the official

R.N.I. (Recommended Nutritional Intake) of 60g is far too low. It is

good enough to prevent scurvy, yes, but not good enough for optimum

health. So here is another sign-post, our Pleistocene ancestors were in

the habit of consuming some five

times the quantity of vitamin C habitually consumed by Americans. We

can be sure that, if vitamin C is constantly in the food supply, the

human body will come to depend on it. Today we fall far short of

supplying that need.

Fiber content at 62 g is some five

times the norm for Americans. We can be sure that our Pleistocene

ancestors never suffered from constipation, colon cancer or

diverticulosis. Also note the quality of the fiber is not a rough,

indigestible, cereal bran, it is all from fruit and vegetables high in

heart-healthy soluble fiber. That’s another straw in the wind –

humans are designed for a high consumption of soluble fibre, not cereal

fibre.

|

Our prehistoric ancestors did not eat:

Milk, cream, butter, cheese.

Bread, breakfast cereals, popcorn, spaghetti, pizza, rice…

Vegetable oils,

Farmed meat (saturated fat).

Sugars (sugar, honey, maple syrup, malt, corn syrup….)

|

A word about tubers and potatoes. A large percentage of our ancestors’

food supply came from vegetation that was prised out of the ground (with

a digging stick) that is, roots, tubers, corms, bulbs etc. A little

known, but common characteristic of all these foods is that they were

all low glycemic.

The tubers had very little starch (instead they had low glycemic inulin).

The potato is a novelty in the human diet. It is high in starch and is

strongly glycemic and insulinemic,

both harmful properties. Regrettably the potato, although botanically a

tuber, cannot be classed with the plant foods to which humans are

naturally adapted.

Finally, note the quantity of plant food consumed is some 2kg (4 ½

lb.). This is the volume of

food that we are designed to eat. Today, we eat less

volume, but much higher

calorie-dense foods. This is another major reversal in our naturally

adapted eating pattern. We can be sure that there are health

consequences.

Thus for hundreds of millennia the pattern remained the same. The

climate didn’t change, the food supply didn’t change, and our bodies

didn’t change. The eating patterns remained sensibly the same: fruits,

nuts, berries, roots, vegetation and, yes, the occasional egg, insect,

grub and small game animal.

The Pleistocene diet was:

.

high in volume

. low calorie density

. high in micro-nutrients

. high in fiber

. very low fat

. low glycemic

. low salt

|

This

process went on down the millennia in a slow rhythm in which the

evolution of Man was sensibly in harmony with his slowly changing

environment. His biochemistry was in equilibrium

with the fuel furnished by his foraging . Like every other creature, he

fed from what was naturally available.

His body was naturally adapted

to his food supply.

The main characteristics of this food supply were high volume, low

calorie density, low fat, high in nutrients and micro-nutrients – and

it was low glycemic index (more of that later).

These ancestors of ours were very successful. They multiplied and spread

out over the whole of Africa. By 50,000 years ago they were crossing the

land bridges into Asia, Europe, Australia and finally the Americas. By

about 15,000 years ago the world was filled up. They were still

wandering foragers needing 200 to 300 square miles per group.

We can imagine the scene – still multiplying, groups becoming too

large and needing to split up, but having nowhere to go except fight

another group for its territory. Some groups found themselves in the

most inhospitable and unlikely ecological niches, like the circumpolar

Eskimos of the Arctic, and the Touareg of the pitiless Sahara desert.

Others, like the Polynesians, undertook ever more daring voyages to

uninhabited islands. But inexorably, the world filled up and there was

nowhere else to go.

Then one year, about 10,000 years ago, in a corner of what is now the

border of Turkey and Iraq, something extraordinary happened. A small

band of these early foragers took

control of their food supply. They stopped wandering and they planted.

It meant staying in one place, protecting the crop, and inventing

fences, hoes, drills, baskets and pots. It meant devising methods of processing, conserving and

storing the crop. Finally, it

meant inventing cooking. With

these big changes coming such a short time ago in evolutionary terms,

our bodies have not at all adapted to them.

Taking control of their food supply solved at a stroke the problems of

overpopulation. Instead of 200 square miles, this group needed only 2 square

miles to feed themselves. They had become farmers. This allowed much

greater densities of population, and the growth of villages, towns, and

cities. But there was a price to pay, as we shall see. Finally, over

6,000 years ago these peoples entered the eras of the great

civilisations of Sumer, Egypt and Babylon. And that is where the history

books begin.

This ‘farming revolution’ spread, during several thousand years, to

almost every corner of the globe. That is to say that most peoples, all

over the world, took control of

their food supply, wherever they happened to be.

And, in taking control what happened? They cultivated not the crops that

they were used to eating, but the crops that it was possible to cultivate. They favoured the crops that were easy to

grow, protect, harvest, and store. That is, crops that were convenient

and practicable.

As time went by, they also domesticated

wild animals. Instead of the wide range of animal matter consumed

before – caterpillars, locusts, ants, lizards, snakes and small game

-- they bred and raised a much smaller

variety of very different

animals, the cattle, sheep, pigs and fowl of today. These animals were

chosen only because no other creature could be domesticated.

For the first time man started eating two kinds of new food: carbohydrates

with high glycemic index, and meats high in saturated fat. In addition,

some tribes, the Mongolian nomads and Aryan pastoralists in particular,

introduced dairy products. For

the first time too, man started cooking

in a big way.

As the societies became richer, they could afford to be more frivolous.

They cultivated crops and raised domesticated animals that were tasty, prestigious, and amusing.

Such is the progress of this trend that, today we eat foodstuffs almost

exclusively because they are convenient,

tasty, cheap and attractive. We have lost all touch with the eating

patterns for which our bodies were designed.

Today, we have lost touch with the eating patterns for which our bodies

were designed.

|

Evolutionary History tells us

that our pre-historic diet contained:

soft vegetation, fruit, nuts, insects, flowers, gums, carrion, some

egg and some small game.

Our Prehistoric diet did not contain:

seeds, grains or cereals, dairy products, farm meat, saturated fat or

vegetable oils.

|

That is a synopsis of what we understand about our pre-historic

ancestors. This information can be compared to what we know about

peoples that still lived in the same way in recent memory.

The great European explorations and expansion of the last few centuries

put an end to the few extant forager lifestyles. . Acculturation by

contact with the West changed these primitive peoples’ way of life

forever.

Nevertheless, it has been possible to piece together historical accounts

for some of the early contacts. For example, until 200 years ago, the

Australian Aborigine still lived the foraging life-style. This applied

to the whole continent – the size of the U.S. – which stretched from

the cold temperate regions of Tasmania to the tropics of Queensland and

the Northern Territories. It is estimated that even though the continent

was filled to saturation, there were no more than 800,000 aborigines.

The first European colonists of Australia were English convicts

sentenced to “transportation.” Some of them escaped from captivity

and lived wild with the Aboriginals. Later, their experiences were

recorded by researchers. Other evidence comes from the first pioneers

and missionaries to the ‘outback’. They observed the aboriginals as

they pushed back the frontier. Later researchers have worked with

semi-traditional Aborigines to download their remembrances of times

past.

All these accounts are helpful and point in the same direction. However,

we must also recognise that these accounts were gathered under

unscientific conditions and that as such, they have to be treated with

more caution.

Similar remarks apply to other pre-farming peoples such as the Eskimo

the Plains Indian.

Attempts have been made in recent years to study so-called

hunter-gatherer tribes like the Ache of Paraguay and the Bushmen of

Southern Africa. ‘So-called’, because they have been influenced by

proximity to the modern world, and they inhabit marginal ecological

niches untypical of our hunter-gatherer forebears. Even so, useful and

indicative data are obtained by researching them. There is not the space

to discuss these data here, but there are several useful references in

the bibliography.

Pre-farming peoples

The

Australian Aborigine

The

Australian Aborigine was the archetypal Pleistocene-type forager (or in

common parlance ‘hunter-gatherer’). His lifestyle has been closely

studied. He was wise enough to never adopt agriculture, although he knew

about the techniques from visiting Asian fishermen. The Australians

lived in small groups of about 35 to 50 souls who wandered their

territories of 200 to 350 square miles.

Traditional Aborigines had no clothes and no dwellings. Every night they

pulled together a rough shelter out of branches. They carried with them

virtually nothing. Everything was improvised for the occasion. Their few

possessions were multifunctional and portable. Spears, woomeras

and boomerangs for the men. Digging sticks and grind-stones for the

women. Always, the band carried a “firestick,” a flaming brand to

set the campfire at night and fire the bush on occasion to trap animals.

They were quite careless about this. Sometimes whole regions went up in

smoke, simply to force out a small animal 50 feet away.

The Healthy Hounzas

Some

of the healthiest and long-lived communities in the world are tribes

that live simply, often in difficult circumstances. The Hounzas, for

example, have excited interest ever since a young British Raj Army

medical doctor, Robert McCarrison, had charge of them in a remote valley

in the High Himalayas. They led a frugal life, cultivating root and

vegetable crops and some apricot trees. Meat and dairy products formed

only 1.5% of their diet.

McCarrison was astonished to find that the Hounzas suffered from no

chronic diseases, that they had vigorous, muscular bodies to an advanced

age, and degenerative diseases were unknown. They kept their teeth

intact for life; that they had an extraordinary resistance to

infections; the men were still procreating at the age of 75, and

apparently lived to 100 years old.

That was in 1904. McCarrison was so impressed that he monitored these

people for another 14 years before returning to London. He found it

difficult to believe, but after eliminating all other possibilities,

reluctantly came to the conclusion that diet was the determining factor.

He became a prestigious research scientist and was one of the first

nutritionists to make himself unpopular by suggesting that white

bread, sugar, meat and dairy products were at the origin of the

average Londoner’s comparative bad health.

|

The

early settlers imagined, falsely, that the aboriginal life was

incredibly hard. But even in the Great Central Desert, the aboriginal

had a wide variety of plant and animal foods. This was demonstrated most

spectacularly and tragically by the fate of the exploring party of Burke

and Wills.

Having traversed the continent from south to north with a huge baggage

train, they finally ran out of food and pack animals in the deserts of

the return leg. They tried to live off the land as the aboriginals did

– but without their detailed knowledge, they grew weaker. Wandering

groups of Aborigines came across them and gave them some help, showing

them how to pound seeds into a cake called “nardoo” for example. The

explorers ate lots of it, but became ever weaker. They ate no vegetation

– they just couldn’t find any tomatoes, lettuce or onions!

The explorers were dying not from starvation but from malnutrition. They developed scurvy, and other deficiency diseases.

Burke and Wills died, but a third member of the party, King, was

luckier. He was found by a group of aborigines and he went to live with

them. This time, he ate the full range of foods available to the

aborigine – none of which was a ‘proper’ food in European eyes.

King survived until rescued by a search party two months later.

All the evidence suggests that, just as for the Great Desert Aboriginal,

our Pleistocene ancestors in East Africa could survive with a great deal

of security in even the most hostile environments. There were plenty of

fall-back positions. If certain favored foods were not available, then

there were always others. And anyway, it was always possible to move on

to another place where there would be yet another range of potential

foods.

It is now believed that famine was an extremely rare occurrence amongst

hunter-gatherers, they just had too many options. Famine is a phenomenon

that came with the farming revolution. One single crop failure could

wipe out a whole people. All their eggs, as ours are today, were in too

few baskets.

What about the children? Infants were breast-fed ‘on demand’ until

the age of at least three years and sometimes four. Solids were only

introduced when the child had teeth to masticate properly. In the

absence of processed foods and formula milk, it could only be that way.

Weaning was started with suitably easy foods like the soft fatty meat

from the tail of a goanna.

|

The aborigine’s feeding pattern changed day

to day and season to season. Sometimes their diet was high in vegetation

with fruits such as ‘bush raisins’, ‘bush tomatoes’, ‘quandong’,

‘bush plum’, ‘mulga apple’, ‘bloodwood apple’, ‘wild

orange’, ‘red apple’, ‘cheesefruit’ , ‘bush fig’; and

vegetation such as water lilies, cycad, palm shoots, pandanas nut, gall

nut, , truffles, bush yams and innumerable edible leaves and roots.

The

Aborigine, like most hunter-gatherers, exploited sources of food that

are not available to other primates – roots and tubers. There was

little competition from other mammals for these foodstuffs and, in hard

times, they often provided the bulk of the diet. Indeed the women’s

digging stick has been called the aborigine’s most important survival

implement. |

Most of the plant foods were eaten raw, although some would be baked in

the ashes of the fire.

At other times, animal matter was important: witchety grubs, locusts,

lizards, snakes, goannas, magpie geese, eggs and, in coastal areas,

turtles, shellfish and file snakes.

Sometimes there was a major kill of a kangaroo, emu, wallaby or, in

coastal areas, barramundi, catfish, saratoga and dugong. This was a time

of feasting when up to 25 pounds would be consumed at a sitting.

Mostly, animal matter was eaten cooked. Small game, snakes, lizards,

grubs and bugs would be cooked whole in the embers of the fire. Larger

animals would be eviscerated and the offal baked and eaten separately.

Animal would be either baked whole or baked dissected. Meat was eaten

‘rare’.

In times of scarcity, the millstone was pressed into service. The

tedious business started of collecting grass seeds, winnowing,

threshing, pounding and grinding. It was so labour intensive that the

aboriginal did it only in times of dire need. In common with other

cereals, the resulting flour had to be cooked to make it digestible. No

pots or pans, just mix the flour with some water, form it into a patty

and bake it in the embers of the camp fire. Those Aborigines who ate

this way too much, had worn and pitted teeth.

|

The Traditional Aborigine diet

is:

.

high in volume

. high in micro-nutrients

. high in fiber

. very low fat

. low glycemic

.

low in salt

Sounds

familiar? |

The

aboriginal had a sweet tooth. A disproportionate amount of his time went

in the searching of ‘sweetmeats’. Honey ants (ants gorged with the

nectar of flowers) were a favourite. In addition there was lerp (sweet insect

secretion on eucalyptus leaves), blossoms and gums. If he was really

lucky he would find a nest of honey bees to smoke out. But these were

rare occasions and the amounts were small.

The

traditional aboriginal was very lean but healthy. His Body Mass Index

was 13.5 to 19. Compare this to the official US figure for healthy B.M.I.

of 20 to 25. The Western target for body leanness is still relatively

plump.

The Aboriginal blood pressure, cholesterol and triglycerides were low.

He had good (high) serum levels of haemoglobin, vitamin B12,

vitamin C and folate. Atherosclerosis was rare. Diabetes was unknown.

All this came to an abrupt end when the European colonists arrived some

200 years ago. Very quickly the aboriginal became ‘acculturated’.

Flour, sugar and rice were distributed to the aboriginals by well

meaning mission stations. Sugar was eagerly sought. Consumption rose to

12 pounds per head per week.

Soon, tinned meat, tinned fruit, biscuits, confectionery and jam joined

the list - to say nothing of alcohol and tobacco.

What

has happened to the Aboriginal’s health? He now has very high rates

of: obesity, atherosclerosis, diabetes, dental caries, and ischemic

heart disease. His life expectancy has dropped to 20 years fewer than

his Caucasian counterparts.

Trials have been made where Aboriginals suffering from these

degenerative diseases were returned to traditional life patterns. Almost

miraculously, within the space of weeks, their health returned.

The aboriginal has traded his calorie-poor, nutrient-dense diet for

exactly the opposite: a calorie-dense, nutrient-poor diet. And he did

this with alacrity. It is a lesson for all of us that our instincts in

matters of nutrition cannot be trusted.

Our instincts in matters of nutrition cannot be trusted!

Native Americans

A similar fate awaited many other peoples when they came into

contact with the western dietary habits. In the United States, the

Native Americans suffer in a similar way. Rates of obesity, diabetes and

cardiovascular disease are much higher in this population. The much

studied Pima Indians of Arizona have one of the highest rates of these

diseases in the land. Trials with Navajo Indians have shown that when

they return to traditional tribal patterns of eating, all their health

indicators return to normal. Blood pressure, diabetes, obesity are all

controlled.

The Eskimo

The

Eskimo is an example of a race which lives in the most extreme of

unpropitious environments. With virtually no vegetation and winter

temperatures dropping to below -40°F,

he lived out the greater part of his life eating fish, seal and whale.

In spite of that, he had low blood pressure and low rates of heart

disease. He got his vitamins from eating the skin of the seal and the

stomach contents (lichens and mosses) of the caribou. He ate every part

of the animal – brains, intestines, blood, even the faeces. Almost

always it was eaten raw. Living above the tree line, a campfire was a

rare luxury.

He

cut off the blubber from his kill (seals, whales etc.) for use as

lighting oil and other external uses. Seal and whale meat shares similar

characteristics with our ancestral wild game. There is little fat in the

muscle meat (little ‘marbling’), and it is particularly rich in

essential fatty acids. As if

that were not enough, the Eskimo high fish diet gave him eicosapentanoic

acid - a great heart protector.

In fact it was perhaps too much of a good thing. Typically Eskimo

bleeding time was high and they suffered from difficult-to-stop

nosebleeds.

|

The Eskimo diet is very high in animal

protein, calcium and Omega 3 fats.

The high animal protein provoked accelerated ageing and osteoporosis.

The Omega 3 oils in the flesh however, protected him from

cardio-vascular disease.

|

We

can learn something too from his high calcium intake of up to 2,000

mg/day. In spite of this mega-dose of calcium, the Eskimo suffered bone

demineralisation and osteoporosis.

Isn’t this counter-intuitive? Today, we know that the culprit is the high meat diet. (The mechanisms are discussed in Chapter Eight.)

The

Eskimo

is an example of a race which lived successfully enough with very

little in the way of fruit and vegetable in the diet. Nevertheless, his

life expectancy was low - around 50 years. The Eskimo died of

accelerated ageing.

Today, with westernisation, the Eskimo has suffered the same fate as the

other hunter-gatherers. He suffers from obesity, heart disease, diabetes

and high mortality. Life expectancy has dropped even lower, to around 35

years.

|

Hunter-Gatherer Studies tells us that a favorable diet contained:

soft vegetation, fruit, nuts, insects, flowers, gums, some egg, some

seafood and some game.

It did not contain:

seeds, grains or cereals, sugars, dairy products, farm meat, saturated

fat or vegetable oils, salt.

|

Forensic Archaeology

Forensic

archaeology is the science of detecting and deducing from archaeological

remains. For example, skeletons and their habitat are analysed for

various periods in human history. Forensic archaeologists can deduce a

surprising amount from these remains.

The Dwarfing of the Human Race.

One

clear and easy result is the comparison of skeletons today and in

pre-farming times. Our Pleistocene ancestors had an average height some

6 inches greater than their descendants who took up farming. Today, in

the opulent but still malnourished West, we have recovered only about 4

inches of the deficit. Maybe this comes as a surprise to hear this. We

do not realize how much our impression of past standards of living is

highly conditioned by our image of life in the Victorian cities of the

industrial revolution. Dickens and Hugo did such a good job in drawing

attention to the wretched conditions that, even today, those images

linger in our subconscious.

We have made huge progress since the nadir reached in the times of

Dickens, but we are still a way from regaining the healthy lifestyle

conditions enjoyed by our pre-farming Pleistocene ancestors. The only

reason stopping us, in these times of plenty, are our own poor feeding

choices.

The reality is that farming radically changed our ancestors’ eating

patterns for the worse.

The responsibility is now within our own grasp to make wise feeding

choices.

The whole of recorded history is a story of the struggles of

populations for ‘living room’. There was always more population than

land to support them. This did drive the incredible progress in

extracting more and more food from the same land. But there was always a

time lag.

Furthermore, under these pressures, humans were spreading into lands and

climates for which they were not at all adapted. It is a great tribute

to their ingenuity that farmers scratched a living in Northern Europe.

But scratching was all it was. Our ancestors over the past couple of

thousand years were in general malnourished - much more than their

ancestors of 10,000 years earlier.

Our recent ancestors were malnourished compared to our Pleistocene

forebears.

The Ancient Egyptians ate:

Fruits – apple, carob, christ’s thorn, egyptian plum, fig,

grape, hegelig, juniper, olive, argun palm, date palm, persea,

pomegranate, sycamore fig, water-melon and many more.

Vegetables – garlic, onion, radish, turnip, bulbs, agrostis,

celery, cress, leek, lettuce, purslane, goats beard, saffron, water

chestnut, cucumber, okra, gourd, and many more.

Legumes – beans, chick pea, lentil, lupine, pea and vetch.

Animal Matter -- ox, sheep, boar, heron, Nile perch and many

more. |

The

Drudgery of Early Farming:

Analysis

of the skeletons of those who took up farming, shows that they must have

done it under considerable duress. It was that,, or die of famine. Their

skeletons show signs of osteo-arthritis,

carpal tunnel syndrome, and collapsed vertebrae. Why was this? It

was due to the drudgery of grinding grains, from morning till night,

between two slabs of stone. And, in view of the bone deformities that

they suffered, even the youngest children were pressed into service. In

pre-historic times no one lived on grains from choice.

In pre-historic times no one lived on grains from choice!

Early Nutritional Diseases:

We have extensive evidence from early Sumerian and Egyptian sites

over 4,000 years ago. It is quite remarkable that the Ancient Egyptians

have left us a legacy of sumptuous burial tombs (the pyramids) with

inscriptions of their daily life. As a bonus they left the embalmed

mummies, accompanied by daily artifacts, for us to analyse.

Even the ordinary folk, who were simply buried in the sand outside the

cities, have been preserved by the dryness of the environment. We

therefore know quite a lot about their state of health too.

Typically populations, as they developed farming, gradually developed

degenerative diseases. The wealthy Pharaohs of Egypt, gorged themselves on

bread, honeyed cakes, ox, game, fowl, fruits, figs, dates, wine and beer.

Not surprisingly, they suffered from obesity,

atherosclerosis, diabetes, and gallstones.

We

know that the ordinary people, who typically ate vegetables, rough whole

bread, olive oil and figs, were on the whole lean and healthy. However,

all classes suffered from gum

disease and dental cavities

and abscesses. This is put down to the high consumption of bread.

All classes suffered worn and pitted teeth from the high grit content of

the flour.

|

Ancient peoples benefited from:

fruits, vegetables and nuts

wild game and fowl in moderation

Ancient peoples suffered from:

bread, honey

farmed meat

Ancient peoples did not consume:

milk, butter, cheese

corn oil, sunflower oil, safflower oil |

All

classes suffered too from parasites such as guinea worm and river

blindness. The Egyptian civilisation was particularly vulnerable, being

built upon the Nile and its regular floods.

As techniques ‘improved’ for making bread lighter, and the taste for

whiter bread became popular, so dental

cavities (ca) makes its first appearance. Dental caries was

virtually unknown in the times before the invention of bread.

On the other hand there is a notable absence of diseases such as syphilis,

cancer, tuberculosis and rickets. This gives us pause for thought.

How is it that not one of the tens of thousands of mummies examined

shows signs of cancer? The answer will come later in the book, but we

can be sure that the predominant reason is that some aspect of the

ancient Egyptian diet was protective.

Studies of Early Civilisations show that:

Fruit, vegetables, salads, nuts, some fish are helpful.

Farm meat, saturated fat, dairy

products, vegetable oils, refined cereals, sugars, are harmful.

|

Epidemiological (Population) Studies

Mankind

has shown immense adaptability and ingenuity as he has spread out all

over the globe. He has had to live under conditions

to which he is not at all adapted. It is like a vast laboratory where a

multitude of different experiments are going on simultaneously. We can

analyse the different lifestyles and compare them to the health

consequences that result.

In the last few decades, the eating habits of whole populations have

been studied. Links have been sought between these habits and the

measured incidence of various diseases and illnesses.

This graph of Life Expectancies for a variety of countries throws up a

number of interesting points:

American men have the lowest life expectancy of the countries shown

Chinese men have a higher life expectancy than Americans - even though

in China the means of keeping old people alive for many years simply

don’t exist.

Chinese men, when they migrate to Hong Kong (HK) where medical support

is to Western standards, have the longest life expectancy in the world.

(Hong Kong is almost entirely populated by recent Chinese migrants.)

Women live longer than men.

The Japanese have, with the Hong Kongers, just about the longest life

expectancies in the world.

It is statistics like this that give epidemiologists plenty to ponder.

|

The Japanese incidence of the

following ailments is a tiny fraction of that for Americans:

heart disease, colon cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer, diabetes,

and high blood pressure

The Traditional Japanese diet is rich in vegetables and fruits. It

contains:

little or no meat;

some fish;

some rice

has no dairy products

It is extremely low fat.

|

The

Japanese

Japanese men have a life expectancy 4 years greater than Amercans.

But only on condition that they stay in Japan.

When Japanese migrate to America and adopt the American ‘way of

life’ including its diet, their life expectancy drops to the American

norm and they get the same diseases.

At home, by a fluke of culture, geography and good luck, they have hit

on a good eating pattern. (see box). But even so, it is not perfect. For

example, the Japanese high consumption of salt (in soy sauce) gives them

a high rate of death from stroke.

The Japanese traditionally consume rice as a staple. Rice is ‘empty

calories’ having a low micro-nutrient and low protein content.

Rice’s glycemic index, however, is better than Western staples (wheat

and corn) and falls in the ‘Borderline’ category. The Japanese

regard rice as being a low quality ‘filler’ (which it is) and feel

bad about serving up large quantities of it. Unknowingly this cultural

pressure is health-helpful as is its substitution by plant food where

possible.

Traditionally, the Japanese are Buddhists, and as such they do not eat

meat. However, they do eat fish. So by chance, they discard a harmful

foodstuff and pick on a helpful one. Even so, they do make one mistake,

they often eat the fish raw. As a result, the Japanese suffer

significantly from various intestinal worms and parasites.

Rapeseed (colza) has been cultivated for millennia in the far East and

the Japanese have been using colza oil as their chief source of fat for

at least 2000 years. Again, by coincidence, they have adopted a

‘good’ oil. Even soy bean oil, also present for some time in

their cuisine, is less bad than most of the alternatives that we use in

the West.

Thus the Japanese have a good diet and it protects them from a

widespread bad habit –

smoking. Nevertheless, there are things they could do even better –

like reduce salt consumption and reduce the consumption of soy products.

The

Cretans

Similar observations have been made with the peoples of the

Mediterranean northern rim. The Cretans, (whose statistics boost the

Greek life expectancies in the graph) had one of the highest life

expectancies in the world, in spite of a hard lifestyle.

This so-called ‘Cretan’ or ‘Mediterranean diet’ has gained a lot

of currency - and rightly so. Its consumption

profile is much closer to the ideal for human beings.

Note that this so-called Mediterranean diet contains no spaghetti, pizza

or medallions de veau. Coincidentally, the Cretans use an oil (olive)

that is neutral in its health impact. Less well known is their high

consumption of purslane. This

is a plant that used to be well known both in Europe and in North

America. What is so special about it? It has a remarkably high alpha-linolenic

acid content. The full significance of this is explained in Chapter Five.

Again, by chance, the Cretans have hit upon a plant food that supplies

the essential fatty acid, vitamin F2 (alpha-linolenic acid)

in which the average Westerner suffers a deficiency disease.

Sadly, with the advance of prosperity and the crumbling of old

traditions, both the Japanese and the Cretans are adopting Western

eating habits. The deterioration in their health is now being

documented.

|

The Cretan Incidence of

heart disease, colon cancers, high blood

pressure ,and diabetes

are all much lower than in the Northern peoples of Europe and of the

Americas.

How do Cretans eat?

fruit and vegetables - plenty

rough ground bread - some whole bread,

fish - some

goat’s cheese - some

meat, sugar, pastry - little or none

milk, cream, butter, vegetable oil - none.

They drink: wine in moderate quantities. |

Clinical Trials

Literally thousands of clinical trials have been carried out to test

various hypotheses about food and its physiological effects. A sample is

given below:

The Lyon Diet Heart Study

A group of 606 heart

attack patients living in Lyon, France, was divided into a control group

and an experimental group. The control group carried on eating as before

a diet typical of Western industrial societies.

The experimental group was told to adopt a Cretan type diet:

more green vegetables, more root vegetables, more fish, less meat

(replace beef, pork and lamb with poultry), no

day without fruit, and replace butter and cream with a special

margarine made from canola oil. All other fats were replaced by olive

oil and/or canola oil. Moderate wine consumption was allowed.

After 27 months

the death rate of the experimental group was so dramatically lower than

the control group, that the experiment was stopped early so that the

control group could benefit from this knowledge.

|

Lyon Diet Heart Study

|

|

Cardiovascular

Deaths

|

Control

(Western)

|

Test

(Cretan)

|

|

Sudden

deaths

|

8

|

0

|

|

Other

deaths

|

8

|

3

|

|

Total

deaths

|

16

|

3

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non fatal

heart attack

|

17

|

5

|

|

Cretan

diet saves French lives

|

All this is to do

with the Cretan or ‘Mediterranean’ diet. It is a way of eating which

is demonstrably heart healthy. Yet there are other organs and diseases

to consider and, as we shall see later, there are some significant

improvements that are still to be made.

Summary of Clinical Trials

Thousands of

similar clinical studies have been carried out. The main lessons are

distilled into these schedules:

|

Helpful Foodstuffs

|

|

Foodstuff

|

Harmful Effects

|

Diseases Inhibited

|

|

|

|

cancers

|

|

fruit

|

|

heart

disease

|

|

vegetables

|

|

high

blood pressure

|

|

salads

|

|

infectious

diseases

|

|

tubers

|

|

bowel

diseases

|

|

berries

|

NONE

|

constipation

|

|

nuts

(moderation)

|

|

indigestion

|

|

fish,

oily (moderation)

|

|

diabetes

|

|

wild

animal matter )

|

|

obesity

|

|

(moderation)

|

|

arthritis

|

|

|

|

osteoporosis

|

|

|

|

Harmful Foodstuffs

|

|

Foodstuff

|

Harmful Effects

|

Helpful Effects

|

|

|

cancers

|

|

|

|

obesity

|

|

|

farm meat

|

heart disease

|

|

|

dairy products

|

osteoporosis

|

NONE

|

|

saturated fats

|

constipation

|

|

|

bulk vegetable oils

|

indigestion

|

|

|

sugars

|

allergies

|

|

|

starches

|

auto-immune diseases

|

|

|

|

high blood pressure

|

|

|

|

stroke

|

|

|

|

infectious diseases

|

|

Doesn’t

this seem familiar?. And isn’t it extraordinary that there is no

disease that can be imputed to a high plant food diet? The full impact

of these helpful/harmful foodstuffs on health is documented in Chapter Eight,

The Food/Disease Connection.

Creatures With Human-Like Body Plans

Another helpful tack is to look at creatures who are built to similar

body plans to ours. These creatures are the class known as primates, the

great apes, being the most like us. From DNA analysis we now know that

we share over 98.0% of our genes with both the chimpanzee, and the

gorilla. Our basic anatomies and biochemistry are almost identical.

|

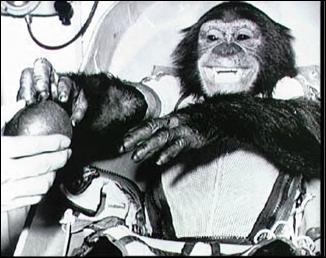

Astronaut Chimpanzee ‘Ham’ grabs a fruit.

He looks pleased to return to Earth after his Mercury space-flight. Ham

was pioneering for Alan Shepherd.

Courtesy: NASA |

For these reasons researchers, after they have first tested mice and

guinea pigs, try a new drug on a chimpanzee for a final check. If it

works on him, and is harmless to him, then that is the nearest proof

possible that it will be fine for humans too.

It is by studying the great apes, that we can learn a lot about how

human bodies work, too.

The great apes live in tropical rain forests and eat what they find

there. Tropical rain forests don’t have marked seasons. Vegetation can

be flowering, fruiting, seeding and regenerating at any time of

the year.

Nevertheless, there is a rhythm of drier and rainier seasons which mean

that there are times of plenty and times of food stress.

The great apes have a very wide territory and they roam around it like nomads foraging for

food. Every night they make a nest in the trees out of branches bent and

broken into place. Great apes are messy creatures leaving excreta and

debris as they go. Being forest nomads, they have never had to develop a

sense of neat housekeeping.

The

Opportunistic Chimpanzee

We know that chimpanzees have similar social structures to us. They

have family quarrels, power struggles, intrigues, alliances, deviousness

- and loyalty and devotion.

From studies in the wild we know how they eat. They live in tropical

African forests and they are still largely tree dwelling. Chimpanzees

eat what they find in trees. That is to say fruit (mostly), vegetation,

flowers, gums, nuts and berries. They will opportunistically eat all

kinds of things if they come across them: birds’ eggs, grubs, termites

and other bugs. The Chimpanzee is a curious creature, ready to try most

things, but also quite fussy. He will inspect his food carefully,

removing any offending part before consuming it.

Chimpanzees will occasionally even hunt small mammals such as infant

monkeys. They hunt as a team, corner the monkey and then, between them,

kill the monkey by tearing it limb from limb. Unlike true carnivores,

chimpanzees don’t have (as

humans don’t have), naturally endowed killing weapons such as needle

sharp teeth or razor claws.

These hunting expeditions are rare occurrences and had never been

observed until the 1960’s. They happen at a precise season of the year

and seem to be linked to male power struggles and the seduction of

females. At such times, the percentage of meat rises to 30 - 40 % of the

diet. There are other periods of the year when no meat is consumed at

all. Averaged over the year, it has been estimated that 90% of a

chimpanzee’s diet is vegetable matter, with a high emphasis on fruit.

Chimpanzees range widely to obtain their food, particularly up and down

mountain-sides, to get a variety of vegetation from the different

altitude zones. They go out of their way to do this, as though they know

that their nutrients are not to be found in just one spot.

The Stolid Gorilla

|

400 lb.

Gorilla

Typical Day’s Consumption

in Captivity

|

160 lb.

Human

|

|

Foodstuff

|

Amount

|

English

|

Grams

|

|

lettuce

|

3

heads

|

3

lb.

|

480

|

|

celery

|

3

bunch

|

6

lb.

|

1,000

|

|

apples

|

6

items

|

1.5

lb.

|

250

|

|

oranges

|

6

items

|

2

lb.

|

320

|

|

bananas

|

3

items

|

1.5

lb.

|

250

|

|

carrots

|

3

items

|

1

lb.

|

160

|

|

kale

|

3

bunch

|

6

lb.

|

1,000

|

|

cantaloupe

|

1

item

|

3

lb.

|

480

|

|

nuts

|

4

oz

|

4

oz

|

40

|

|

raisins

|

8

oz

|

8

oz

|

80

|

|

corn

|

8

oz

|

8

oz

|

80

|

|

pecans

|

4

oz

|

4

oz

|

40

|

|

sweet

potato

|

3

items

|

1

lb.

|

160

|

|

tomato

|

2

no

|

0.5

lb.

|

80

|

|

Totals

|

|

26.5 lb.

|

4.5 kg.

(10

lb.)

|

|

For comparison purposes, the quantities are scaled down for a 160

pounds human. Even so it represents ten pounds of food intake per

day. Humans are not gorillas and it is not suggested here that we

should slavishly model our eating patterns on them. All the same,

humans can and do eat like that and vegans can draw inspiration

from this vegan feeding pattern. They should replace much of that

pasta, bread, potato and cereals by high micronutrient density

plant food.

|

The gorilla is a total vegetarian. Although an adult male weighs 400

pounds. of solid bone and muscle, he lives entirely on the fruits and

vegetation found in the tropical rain forest. A gorilla will not eat

bird’s eggs should they be right next to him.

The

gorilla gets all his nutrients from what he eats, chiefly vegetation,

what we would call leafy green vegetables and salads. His diet also

includes nuts, flowers, mature leaves, twigs, and gums. Protein comes

entirely from the vegetation; energy from the carbohydrates in the fruit

and vegetation; vitamins and minerals (including calcium and iron) are

all present in perfectly healthy quantities.

Look at the table above. It is the food typically consumed in a

day by a gorilla in captivity. This particular menu has been chosen

because it contains only foods that humans eat too. That gives a direct

comparison for what a human might consume on such a typical day. In

practise, over a period of time, a gorilla will be eating even in a zoo

a huge range of plant foods including gums, flowers, branches and twigs.

In the wild, the gorilla would not be eating raisins, sweet potatoes, or

corn. The zoo-keeper clearly has not heard of the Natural Eating

Pattern. In mitigation, note that these non-primate foods form only a

small proportion of the total intake.

The gorilla ranges less widely than the chimpanzee. He is less fussy and

is more of a slow-moving vegetation processor. With all that food he has

got to eat, he just keeps stuffing down whatever is closest to hand!

A fully grown male gorilla, although a vegan vegetarian,

weighs 400 lb.

of solid bone and muscle!

The Great Ape Diet Summarised

The chief characteristic of the great ape diet is that it is high in

volume low in calorie density, rich in micro-nutrients; high in fiber

and very low in fat. There are no: cereals, dairy products, bulk fats or

oils, fish, or starches. There is virtually no meat. Sounds familiar?

The great apes spend quite a lot of time eating, up to 30% of their

waking time, even more for the gorilla. Their eating pattern is to start

foraging in late morning and then ‘graze’ at regular intervals. That

is to say, they eat little but often. But it is worth repeating, they

are snacking on low calorie-density foods. If proof is needed, they

hardly ever drink. The water content of their foodstuffs is greater than

80%. At this level the great ape can maintain a positive water balance

without consuming water.

|

The

Great Ape Diet:

high volume

low calorie density

rich in micro-nutrients

very low fat

low glycemic

Sounds

familiar?

|

The Natural Eating Pattern

When

we look at all these sources of evidence, and “connect the dots”, we

get the picture of the Naturally

adapted eating pattern – the pattern of eating appropriate to the

human species:

The Naturally Adapted Eating

Pattern is:

High

Volume,

High Fiber

Low Calorie Density

High Micronutrient Density

Low Glycemic

Low Fat

Low Salt |

|

The Naturally Adapted Eating

Pattern is to:

eat little but often

only start eating in the morning when ready

eat lightly or not at all in the evening |

The Naturally Adapted Eating Pattern does

Contain:

Vegetable matter (salads and vegetables) - lots

Fruit (low glycemic) - lots

Tubers, roots (low glycemic) - moderately

Wild Animal Matter - moderately

Nuts - some

Pulses - little or none |

The Naturally Adapted Eating Pattern does

not Contain:

Cereals (wheat, bread, corn, rice, pasta, breakfast cereals, etc.)

Vegetable Oils (sunflower, corn, safflower, peanut, palm oil, etc.)

Dairy Products

Farm Meat (beef, lamb, pork etc.)

Sugars (sugar, malt, malto-dextrin, maple and corn syrup, honey, etc.) |

What does this mean in practical terms? After all, our ancestors walked

barefoot. They also never washed and lived in what seems to us great

squalor. Are we expected to return to that? Of course not.

The whole point about Natural Eating is that we learn the lessons.

Lessons about the genetic programming that determines the harmonious

eating pattern for our bodies. We can identify those aspects that are

important and those which we can steer around. In other words we can prioritise.

And just because a food is new to the diet, doesn’t mean that it is

condemned out of hand. It just has to prove itself before it can be

admitted to the club. For example, legumes, tomatoes, cocoa and even

alcohol (under carefully controlled circumstances) get their ‘Green

Cards’.

The job of the next part of this book is to illustrate how this can be

done. How we can get closer to our naturally adapted eating patterns

while living in the modern world.

| Natural Eating is the art, under

modern conditions, of getting close to our naturally adapted eating

patterns.

|

A

hooked wooden stick used for launching a spear with greater force

than can obtained by the arm alone.

|